publications

Partisan Politics. Looking for consensus in Eighteenth Century Towns

by Jon Rosebank

Exeter University Press, June 2021

*See below for a whopping discount exclusive to History Café Listeners.

#57 From mayor to meat market. Getting elected in the 18th Century.

At least until the 1990s historian Lewis Namier’s shadow loomed so heavily over the 18th century that that period – unlike any other - was still being written largely from the papers of central government and the gentry. Historians still considered the period, in the title of a well-thumbed textbook, the ‘aristocratic century.’ According to Namier, for example, the gentry bought their way into a parliamentary seat, mainly by purchasing land, or by gaining the approval of some unrepresentative local patron who had the borough in his pocket. Well, Jon's 1985 doctoral thesis, researched entirely from local documents rescued from mouldy parish chests and corporation vaults, contradicted Namier so baldly that although Jon was awarded his doctorate he could never publish. But now that the old Namier orthodoxy has collapsed and everyone agrees with Jon, he’s been able to bring out his book. It shows just how far the ordinary people of eighteenth century Britain ran rings around the gentry and aristocracy and ran things for themselves.

Listen here.

History Café’s take on Jon’s new book

This is an academic book, being sold at an academic book price! But it’s unique. So we’re shouting about it.

Historians have begun to discover that eighteenth century British communities were extraordinary places. Ignore the nineteenth century reformers’ propaganda about corruption (and the twentieth century historians who believed them, and added that the gentry ran everything anyway). Take eighteenth century towns. Most were small, everyone knew everyone else’s business, most money was raised and spent locally, and a very large proportion of men (anyway) took part in local affairs. Not just occasionally by voting in elections, but every day, doing their bit in unpaid jobs for the local community. This was democracy in motion.

Jon spent 5 years going through the archives of 7 towns to build a picture of real life and real people. His book lets us listen in to the political gossip in pubs, to grasp the market dilemmas of tradespeople and merchants, to share in the drama of local church schisms and the violence of elections. And it shows, in close up and personal detail, that the gentry who got elected as MPs were dancing to the townspeople’s tune. Ordinary folk ran things for themselves.

Synopsis

New understandings of the middle order (precursors of the middle class) and of the post-1688 English Parliament have shifted the focus from Westminster to the constituencies in the study of eighteenth-century politics.

It was the towns, and especially the smaller parliamentary boroughs, that set much of the legislative agenda and which defined partisanship. This is also where religious tension was most intense and enduring.

Yet there has never been a thoroughgoing comparative study of small-town economy, religion, government and politics. Deep in the archives, the history of a clutch of towns in south-west England in the early years of the eighteenth century offers revelatory insights. Their diverse economic structure and religious divisions made these towns extraordinarily difficult to govern, while late Augustan partisanship (reign of Queen Anne 1702-14) spread into the streets and taverns, threatening urban order.

This precipitated heady local realignments, with three or even four factions in each place cutting across Whig and Tory lines in the pursuit of consensus. In this intensely urban politics, government patronage was peripheral; area gentry were drawn in but had little control. The impact of this many-sided partisanship on national politics was profound.

Building a clearer picture of significant change around the time of the Hanoverian accession, this book proposes a fresh approach both to the study of early modern politics and of towns far beyond its immediate region. It will be an important asset to scholars and students of both.

*Exeter University Press are offering an amazing discount for History Café users. Quote the discount code HISTORYCAFE45 to save 45%.

Election Missiles: Cuba and US Votes

by Jon Rosebank

Jon Rosebank writes on the impact of the 1962 mid-term US elections on the Kennedy’s Cuba policy that year.

Cuba Solidarity Campaign, September 2020

Pod Bible

Stu Whiffen interviews Jon and Penelope on this bonus episode at the 11:05 mark.

August 2020

‘G.N. Clark and the Oxford School of Modern History, 1919-1922: Hidden Origins of 1066 And All That’

by Jon Rosebank

The English Historical Review, Vol 135, Issue 572, Feb 2020, pages 127-156

Abstract

W.C. Sellar and R.J. Yeatman’s 1066 and All That is a satirical history of England, published in 1930. It has long been thought to be a parody of popular history textbooks, characteristic of a generation of post-war writers disillusioned with the tone of patriotic English exceptionalism of many books. This paper explores contemporary critiques of history textbooks in the first third of the twentieth century and finds, however, that 1066 And All That is unusual in its implied criticism. It suggests that the standpoint of its authors reflects more than simply the recoil of their generation of ex-servicemen. It proposes that the book reflects their own particular experience of reading history at Oxford in 1919–22, at a time when teaching in the Modern History School still included much that was literary and whiggish. G.N. Clark had been their tutor, a historian close to C.H. Firth, Regius Professor of Modern History, and sympathetic to Firth’s long and controversial campaign for reform. While Clark’s later reputation was as a cautious scholar, as a young man he was a witty iconoclast, active in left-wing politics. We trace his influence on Sellar and Yeatman through the lectures they attended and discover that 1066 And All That bears clear references to Clark’s reformist views on history at Oxford.

We Shall Never Surrender.

Wartime diaries 1939-1945

edited by Penelope Middelboe, Donald Fry and Christopher Grace,

essays providing historical context by Martin Lamb

Macmillan, 2011,

so long ago you may have to buy a used copy

We turned to diaries kept during the second world war to comprehend that period of our families’ lives and our shared history. We chose nine diarists – five women and four men – all living in Britain when the war began in September 1939. We looked for working-class writers to include in the mix but we found none who kept going for the duration. To balance this we include letters and writings from a wide range of witnesses at the end of each seasonal chapter.

George Beardmore (31) a temporary insurance clerk who was afraid of losing his job and being unable to provide for his wife and baby

Vera Brittain (45) mother of the late Dame Shirley Williams and author of Testament of Youth. A nurse in the first world war and now a leading pacifist campaigner but surprisingly on Hitler’s hit list.

Alan Brooke (56) a senior officer in the British Army – eventually Chief of the Imperial General Staff - writing an illegal diary to his wife Benita.

Anne Garnett (30) wife of a country lawyer in rural Somerset and mother of two young girls

Clara Milburn (56) living with her husband near Coventry’s engineering factories – likely to be a target for the Luftwaffe – with a son about to be called up.

Naomi Mitchison (41) author of 20 novels and mother of six children. She and her husband were Labour Party intellectuals and moved to their second home in Scotland for the duration where she became pregnant once more.

Harold Nicolson (53) – MP for West Leicester, former diplomat to Berlin, owner of Sissinghurst in Kent and husband of Vita Sackville West. He opposed Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler. His name was also on Hitler’s hit list.

Hermione Ranfurly (25) – alone in the world after her parents abandon her, her brother is killed in a flying accident and her grandparents die, now married to the sixth Earl of Ranfurly who is called up and posted to Palestine.

Charles Ritchie (32) a Canadian diplomat who’d studied at Oxford and moved in upper-class literary circles.

Edith Olivier: from her Journals 1924-48

edited by Penelope Middelboe with a preface by Laurence Whistler

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989,

only second-hand copies available

Edith Olivier (1872-1948), witty conversationalist and novelist, eccentric daughter of a Wiltshire rector, kept a journal for sixty years. In it she recorded her life as the first woman mayor of Wilton during the second world war, also her friendships with the many young artists she inspired and entertained: Cecil Beaton, Siegfried Sassoon, Lord David Cecil, the American poet Elinor Wylie, and William Walton (who wrote his first symphony whilst staying with Edith. But her greatest friend and protégé was the painter, Rex Whistler.

Penelope spent 5 years transcribing her great, great aunt’s hard-to-read handwriting and producing this book so that these revealing diaries could be appreciated by a wider audience. They have been much quoted since.

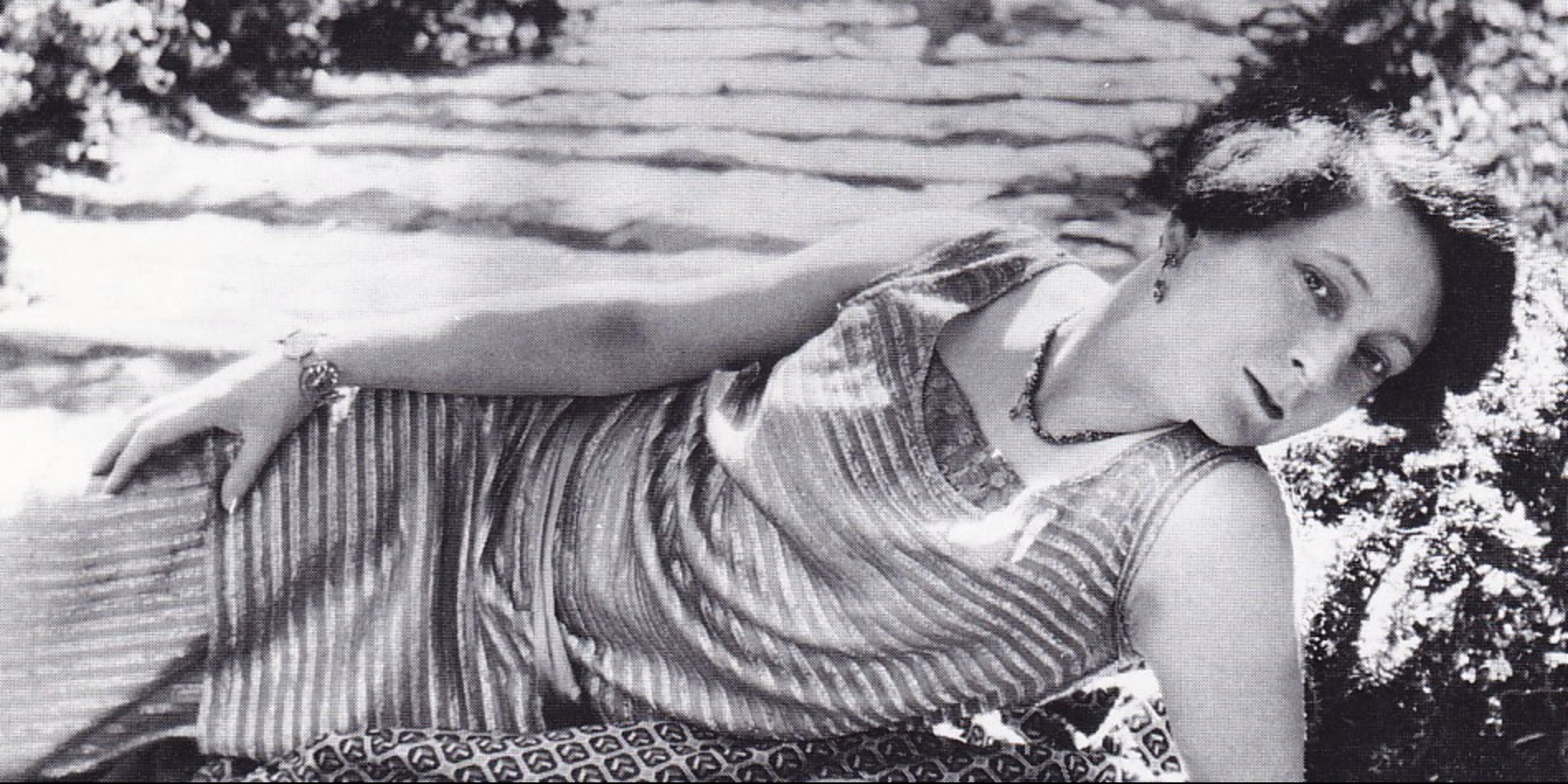

Edith taking a break as Queen Elizabeth, Wilton House pageant

Edith in 1924

Portrait by Rex Whistler of Edith, wartime mayor of Wilton

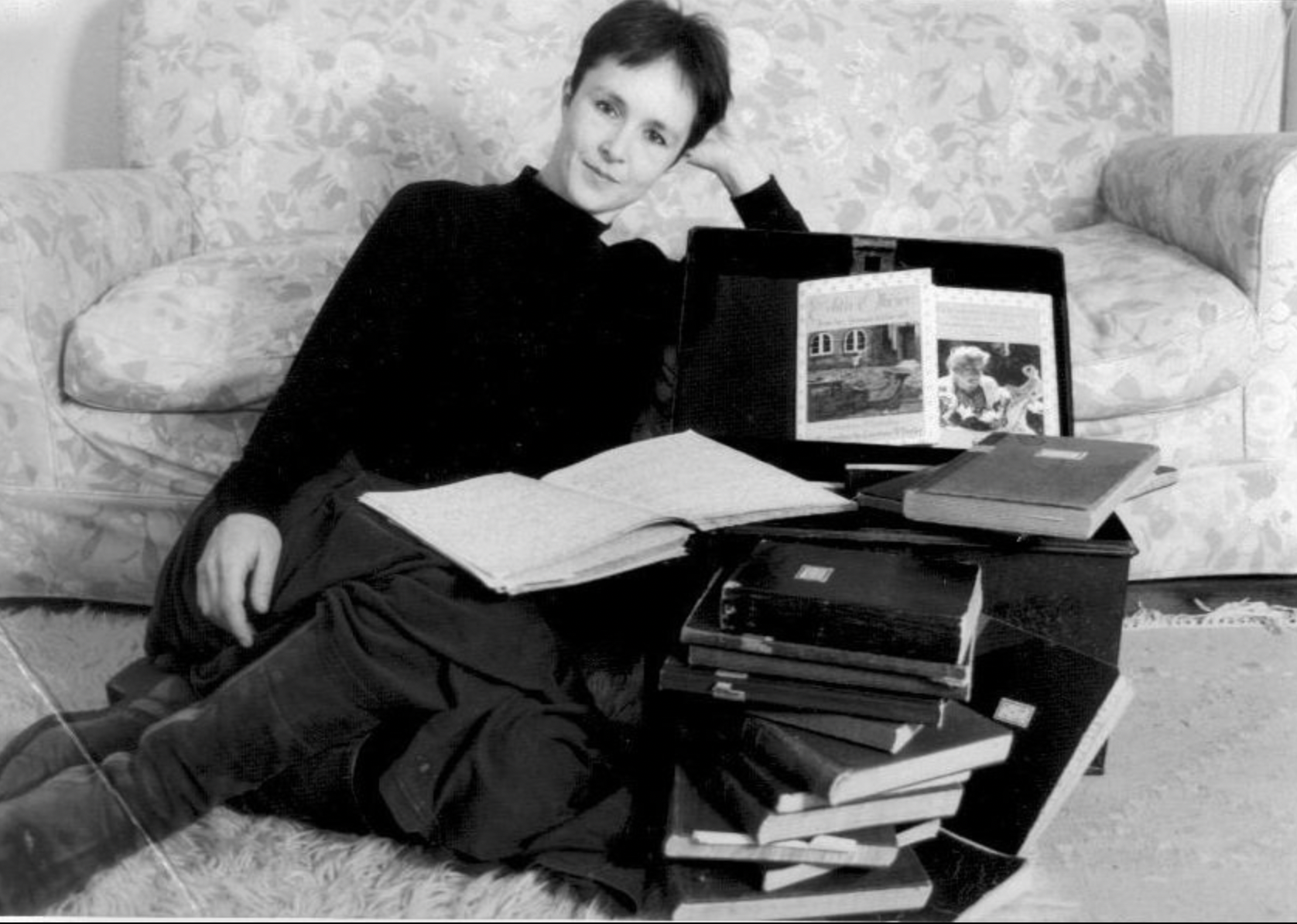

Penelope in 1989 with diaries

Animation

Most of the animated films Penelope was co-script & series editor on can be found for free on YouTube.