Money not morality ended British enslavement

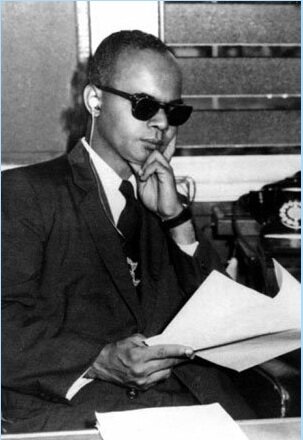

Everyone knows that slavery was abolished in 1833 (in British colonies anyway) because of the moral campaign of William Wilberforce. But this is just the story told by his sons in a five-volume biography published after his death. In reality Wilberforce had been a saintly but often ineffective campaigner and the lead had really been taken by others. Much more important, in 1944 Eric Williams, Trinidadian historian (who’d got the top history first in his year at Oxford and became the first PM of Trinidad and Tobago), demonstrated in Capitalism and Slavery that it was economic changes, and not moral campaigns that ended slavery: it ended because it simply no longer turned a profit. It’s a brilliant, persuasive book and sparked a debate that’s still not resolved. We consider both sides.

We start this 5-part series by trying to give a factual outline of the experience of being transported in horrendous conditions from Africa to the British Caribbean against your will. And we open up the debate started in 1938 by the brilliant young Trinidadian historian Eric Williams as to whether it was money or morality that ended British enslavement? The trade in the enslaved was banned in 1807, the enslaved were 'emancipated' in 1833.

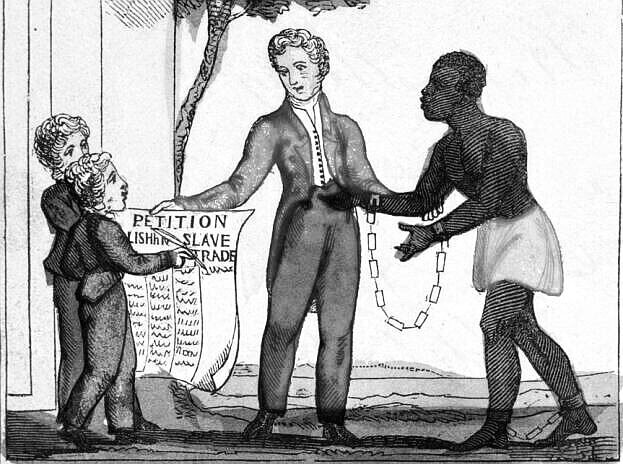

Before we get down to the hard facts of whether or not British enslavement ended because the slave economy no longer worked, we should take a closer look at the moral campaign for its abolition. It turns out to be intriguing, though it was a very different campaign from what we’ve all been told (and many students are apparently still being taught). Credit for the campaign’s success should go to Margaret Middleton and an enormous number of people who aren’t much remembered now. Not just William Wilberforce. The campaign of course stretches from the 1780s to the 1830s.

We look at a map of the British Caribbean to understand why losing the British north American colonies after 1783 mattered to British enslavement. We explore how the trade winds had helped create the four-cornered ‘triangle’ of the British slave trade involving North America, Africa, England and the British Caribbean – and how this doesn't work once this section of the 'Empire' - the North American States - strikes back and becomes 'out of bounds' for British trade. And we begin to see why the British government, having fought at great expense to protect the British Caribbean in the American War of Independence, began to isolate the British planters in the Caribbean and favour the East India Company instead.

When the HMS Lutine went down, 9 October 1799 off the Dutch coast, carrying a million pounds of gold and silver, it led to the collapse of the Hamburg sugar market and within a few years the banning of the slave trade.

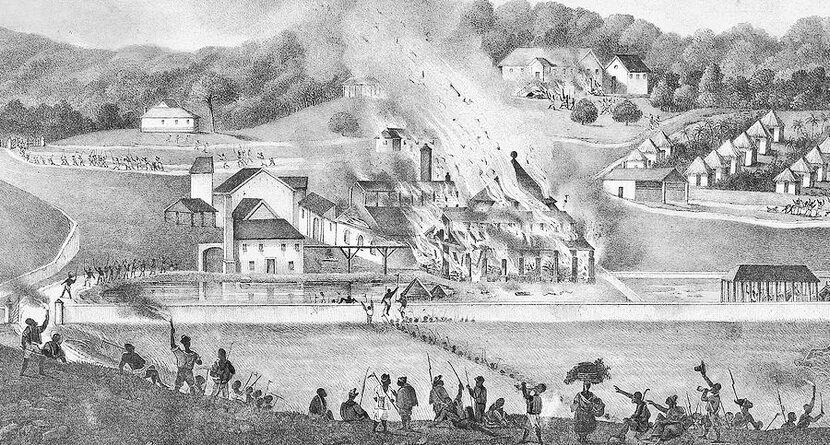

By 1832 it was clear to both the House of Lords and the Commons that the British planters in the Caribbean were dragging the British economy into a credit crash. It looks to us very like the crash of 2008. The Jamaican Rebellion of 1831 and the vicious retaliation by rector George Wilson Bridges and his white supremacist Colonial Church Union in 1832 was the final nail in the coffin of British enslavement. The CCU showed beyond doubt that the Jamaican planters, who had always dominated the West Indian planters lobby in London, were a breed of racist thug who flatly refused to make conditions tolerable on their plantations. But the result was that they would never be commercially viable. Abolition became the obvious solution.

Music: we’re delighted to use extracts from Akoko Nante Ensemble tracks Bamaya and Kpanlogo, using the Akan language from Ghana, as many of the enslaved did. You can find the whole album, recorded live on WFMU’s Transpacific Sound Paradise 6 Feb 2016 here. Free Music Archive, Creative Commons license here.

There is an enormous number of books and papers on enslavement, more than we can possibly outline here. The subject even has its own learned journal, Slavery and Abolition. We read over 60 titles and made nearly 85 000 words of notes. So we’ll just try to open a few doors to get you started…

We also found it a great help, as we explain in the series, to have a map of the British Caribbean or West Indies as it was then called.

Matthew Wyman-McCarthy has written an outstanding review of the historiography of abolition for History Compass 2018. It’s short, readable and the best starting place if you can get it.

Emma Christopher’s Slave Ship Sailors and their Captive Cargoes (2006) is your book on the atrocities of the so-called ‘middle passage’, carrying Africans to the Caribbean. To begin to understand what enslavement itself was like, read Michael Craton’s Testing the Chains: resistance to slavery in the British West Indies (2009). It is much more than a narrative of rebellions. It is the best book on the reality of slavery on British Caribbean estates in this period.

Heather Cateau’s essay in Catherine Hall’s edited volume Emancipation and the Remaking of the Imperial World (2014) is good on the realities of enslaved life, revealing its largely unknown transition towards paid labour. The rest of the book seems rather out of touch with current understanding of the period, though there are useful essays by Robin Blackburn and Pat Hudson.

Matthew Mulcahy’s Hurricanes and Society in the British Greater Caribbean (2008) adds a neglected but, as we see in the series, important dimension.

For the abolition campaign, you’ll probably begin with Christopher Brown’s Moral Capital: foundations of British Abolitionism (2006), which is much the best book on the long origins of abolition, including the conflict between missionaries and planters. Brown argues that the Evangelicals like Wilberforce came late to the party and – much less convincingly – that it was mainly a means to win social acceptance for their religious views. But Brown’s book is the best account of the Quakers, Margaret Middleton’s otherwise badly neglected Teston Circle and much besides.

Clare Midgley’s Women against Slavery (1992) reveals the wider extent to which women were beginning to campaign publicly by the late 18th century. Kenneth Morgan’s Slavery and the British Empire (2008) has more good material on the deep origins of abolition. See also JR Oldfield’s Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery (1995). Michael Jirik’s paper in Slavery and Abolition 2020 adds another little-known dimension about the abolitionists in Cambridge. Matthew Wayman-McCarthy’s paper in Slavery and Abolition 2014 is good on the contribution to abolition of William Cowper and John Newton - the man whose life story included being himself the slave of an African slave trader as well as a captain of a slave ship.

Building on Brown’s Moral Capital, you should also read Gareth Atkins, Converting Britannia: Evangelicals and British Public Life 1770-1840 (2019). It’s not only a fascinating story, but it unlocks an extraordinary and neglected layer of British affairs in this period, revealing a web of interconnected Anglican evangelical individuals in government and throughout the Empire. The West Indies hardly get a look-in – but this, we argue, was in itself crucial to the decline of the planters’ influence, given the influence of the Evangelicals everywhere else. For missionaries who did get to work in the British Caribbean, see John Catron’s paper in Church History 2010.

Derek Peterson’s edited Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain and Africa (2010) has an entertaining if patchy essay by Boyd Hilton on the changing ways abolition anniversaries have been marked and arguing (among a scatter of other things) that religion had always been key to the campaign. Philip Morgan’s essay in the same book has some good material on the amelioration of enslaved conditions that was attempted in some islands and also on the ways in which war against the French in the 1790s transformed the situation.

For a revealing parallel, see Erik Gøbel’s The Danish Slave Trade and its Abolition (2016). The Danes abolished the slave trade before the British, but largely for the same reasons. It was uneconomic without heavy state assistance. And that was becoming politically less and less acceptable.

On opposition to the abolition campaign, Christer Petley’s piece in Slavery and Abolition 2018 introduces you to the so-called ‘West Indies interest’ – the planters’ lobby - and the reasons for its progressive weakness from the 1780s. Andrew O’Shaughnessy has also written on this subject. His paper in Historical Journal 1997 and his book An Empire Divided (2000) are full of important details. But they are so confusingly written we despaired of following an argument. O’Shaughnessy appears to believe (we think) that it all comes down to the loss of the planters’ political leverage owing to the loss of the American colonies.

Michael Taylor’s The Interest (2020) is apparently about the planters’ lobby 1807-34. But it ends up being a rather old-fashioned account of the abolition campaign and the planters’ response. It’s probably, however, the most accessible way to start on the later period, and has lots of good stories. Actually, Taylor’s own earlier paper in Historical Journal 2014 gives you a better insight into the changing economic arguments of the planters in this period as they struggled to keep their enslaved workforces.

OK. So we can’t avoid the economics any longer. As you’ll understand from the series, this is all about Trinidadian Eric Williams’s venerable thesis from 1938 Oxford that enslavement was actually only abolished because it no longer made economic sense; and Seymour Drescher’s now also rather aged counter-argument that the West Indian sugar economy was booming, and that abolition was a moral campaign that succeeded even though it was directly contrary to Britain’s economic interest. You have to say, put like that, that any familiarity with history would suggest Williams must be right. No legislature acts against its economic interest. But this has descended into a decades-long argument over trade figures and sugar prices and most historians in the field tend to one side or the other. For that reason, you will need at least to be aware of the debate.

You could look up Eric Williams’s book Capitalism and Slavery (1944 and still obtainable). But it’s more informative, and quicker, to read Pepijn Brandon’s revealing ‘From Williams’s thesis to Williams thesis’ [great title – gets you thinking] in the International Review of Social History 2017 which traces the Trinidadian’s journey from controversial doctoral thesis in Oxford in 1938 to the book published in America in 1944, and makes the whole thing much clearer. Similarly you could plough through Seymour Drescher’s Econocide (1977 – 2nd edition 2010 with an introduction that summarily tries to brush off some of his critics.) The book has a catchy title but is awkward and difficult to read from then on. Better to take a shortcut and read Boyd Hilton’s summary of it in his essay listed above.

You must straightaway then read David Beck Ryden’s excellent piece in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History 2001 which comprehensively destroys Drescher’s case. Ryden’s book West Indian Slavery and British Abolition (2009) has had a mixed reception. But his economic argument – that the planters badly misplayed the economic opportunities of the 1790s – really closes the door. Drescher himself has produced no convincing answer. See also Ryden’s devastating papers in Atlantic Studies 2012, a special edition on abolition, and with Ahmed Reid in the same journal 2013. Selwyn Carrington has also opposed the whole Drescher interpretation, with papers in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History 1987, the Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 1989 and The Sugar Industry and the Abolition of the Slave Trade (2002). Carrington shows that rising debt and the loss of the North American colonies were insurmountable obstacles for the planters. Richard Sheridan is one of the doyens of this field. His paper in the Journal of Economic History 1961 predates Econocide, but is in retrospect an excellent introduction to the collapse of the British West Indian economy. Put Sheridan together with Ryden, Reid and Carrington and we believe it’s impossible to go with Drescher any longer.

In fact Drescher’s calculations now look trivial alongside the complexities that are discussed by specialist economic historians. To see what we mean, have a go at Klas Rönnbäck’s paper on value added in the Journal of Global History 2018. Somewhat easier is Nicholas Radburn’s paper on the extraordinarily complex structures of credit in Economic History Review 2015. Looking after 1807 (and even Drescher would concede that economic factors then kicked in) see Kathleen Mary Butler’s The Economics of Emancipation on Jamaica and Barbados (1995), which has a good section on the economic evidence collected by the Commons Select Committee that met in 1832.

Similarly, as we argue in the podcasts, you really can’t begin to understand the collapse of enslavement without getting to grips with the East Indian empire also. Jonathan Eacott’s Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America (2016) is the book you need. It doesn’t deal with enslavement directly, but is an essential context. Anthony Webster in Economic History Review 2006 also gives you a feel for the financial complexity of the East India trade.

Politics is rightly out of fashion with most historians these days. The immediate politics of emancipation has provoked some old-fashioned micro-studies of extreme tedium and a lot of airy nonsense about how the Great Reform Act somehow put the ‘West Indies Interest’ out of business by banning pocket boroughs. But there’s nothing that truly gets to grips with the bigger question of ‘why then?’ There was a special 2007 edition of the journal Parliamentary History examining the politics of abolishing the slave trade. Rather characteristically for the History of Parliament, it adopts a high political tone: Drescher was completely right and this was all about a moral Parliamentary campaign for abolition. Stephen Farrell’s paper is, for all that, worth reading, partly for excellent details of the hustling behind the scenes, but also because the thinness of the evidence that it was ever a moral victory shows through. But it’s left to David Beck Ryden (2001) to quote the actual speeches that introduced the measure, which were all about the economics.

For the politics of the 1820s, you have to go back to Izhak Gross’s 1980 Historical Journal paper. Trevor Burnard and Kit Candin’s paper on slave owner John Gladstone in the Journal of British Studies (2018) excellently reveals the deep ambivalence of one of the important figures in the later emancipation debate. Otherwise you have to do the best you can with Michael Taylor’s book The Interest, which gives quite a bit of information but ends up largely blaming the pocket boroughs.