episodes

WHAT'S NEW

WHAT'S NEW

Loss, love and the struggle to stay alive in 1912

Jon explains his decision to write an historical novel, A Spring Marrying. He discovered the extraordinary history of the sail trawlers working off the English coast before 1939 whilst making a film for C4. It was the men who crewed them that fascinated him the most. Down in Brixham, Devon, they had four crew – skipper, mate, deckhand, and a cookie who was often only 12 or so. Theirs was an unremitting routine. Danger and death were never far away: it was the most dangerous job in the land. Yet they earned a reputation as supreme, quietly proud seamen, religious, brilliantly able to navigate without charts and survive just about anything. Except, maybe, falling in love with the town’s most complicated young woman.

*Also available through Waterstones where you can post a review whether you bought from them or not.

Start Listening

The series we are currently broadcasting is shown first.

After that, in reverse chronological order - from the present day to 1400 - comes a huge range of subjects. Anywhere a story has got stuck in our collective memory but looks - to us - like it would benefit from a re-visit. These fresh reinterpretations take time to research, argue and record.

You’ll find that each subject page contains a playlist, synopses, photos and read on.

To get straight to the Spotify playlists, head over to our Linktree.

Roman Emperor ‘Constantine’s attempt to ally Empire and Church corrupted the church from what was absoluta et simplex – plain and simple – to a gross caricature’ - 4th Century historian, Ammianus Marcellinus

‘Even wild beasts are less savage to men than Christians are to each other’ - Emperor Julian early AD360s

What we have today is a Church completely reinvented in the 4th Century. It had lost virtually all memory of Jesus’s first Apostles. It still uses its invented ‘historical’ genealogies of bishops of Rome (from St Peter to Leo), to shore up its authority. The reality is much more shocking.

An investigation into the international movement to persuade us there’s just no money left to invest in health, schools, local government, roads or railways. Who master-minded the economic hokum that distorted reality so comprehensively we believe we’ve maxed the national credit card and we have no option but to live in a society without the morality to care for the needy? This is the side of the 1960s and 1970s we’ve never seen before, the crisis that led to the rule of international finance and ‘the twilight of sovereignty.’ [Seven episodes]

October 1962 was the closest we’ve ever come to nuclear war, but almost everything else we’re told about it is propaganda. [Seven episodes]

Did the Germans ever have a joined-up plan for the invasion of Britain? Churchill didn’t think so. But that’s not what he told the British public. And for good reason. [Six episodes]

How on earth did Hitler’s Nazi Third Reich ever find the resources to build a vast army and airforce and launch a war in 1939? Germany was supposed to be financially crippled after the First World War. And in the 1930s Europe was meant to be in the middle of the greatest depression in modern times. So how Hitler’s regime could afford to re-arm itself with the latest technology, and then hurl the world into war on an enormous scale, is a fundamental mystery. Or is it? [Ten episodes]

A moment in history when Wallis Simpson, the abdicated king Edward VIII of England, French fashion, Cecil Beaton, appeasement, USA investments in Nazi Germany, the Spanish Civil War and Salvador Dali come together. And a quietly brilliant palace coup. [Three episodes]

The story of how in just 13 years, Hitler led a fringe sect with less than a hundred members and outlandish ideas to be the dominant force in German politics.

Jonathan Myerson talks to us at History Café about the challenges of bringing this extraordinary and shocking story to life through the eyes of the people closest to him. He tells us how every scene in a long series of 8 plays was based on a real event and that much of the dialogue including Hitler’s speeches comes from contemporary sources. [One episode]

Why did fashion become so much more conservative in the 1930s? We argue the reason wasn’t Schiaparelli or Chanel, but the puritanical Hays Motion Picture Production Code that banned indecent passions in Hollywood. MGM’s Adrian Greenberg was the most powerful Hollywood designer of his day, designing for the camera, experimenting with hats and calf-length dresses that flattered the lead actresses, but stuck to the code, and could be copied cheaply and quickly and sold to ‘Nancy’ in the plush picture-house seat. [One episode]

Published in 1930 and never out of print since, this isn’t (as everyone has always supposed) just an innocent laugh at kids’ mistakes. 1066 And All That is suffused with subtexts. Our original research reveals its origins back in the academic infighting and socialism Sellar and Yeatman experienced in 1919 Oxford. [One episode]

At least 50% of deaths from war in the last three centuries were civilians. In 2001 the International Red Cross calculated that in modern warfare ten civilians die for every member of the military killed in battle. In the two World Wars the vast majority of soldiers were “civilians in uniform” – conscripts or volunteers. But do we officially remember them? [One episode]

There are those who say that the Battle of the Somme (July-November 1916) was one of the British Army’s greatest achievements. They claim that - after the first day, with 57 000 casualties, more than any other day in the Army’s history – the British inflicted such damage on the German forces that they never truly recovered. But we show that this had not been the British Army’s intention. That first day, Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig explicitly planned for a dramatic breakthrough. The slaughter that followed was a direct result of the British Army’s long history of failure to understand modern warfare or to learn from its errors since the war started in 1914. It did not possess the heavy artillery it needed. It was also a result of the blind snobbery of its officers. We throw their ghastly blunders into relief by comparing the brilliant – but little known - success of the French that day and of the few British divisions that copied what the French did. [Seven episodes]

We find that Britain was tricked into going to war in 1914 and it had a lot to do with cycling holidays in France and the Sloane Square Gang. No, seriously, this was a shocking outrage, perpetrated by a few who should have known better. [Seven episodes]

Jon explains his decision to write an historical novel, A Spring Marrying. He discovered the extraordinary history of the sail trawlers working off the English coast before 1939 whilst making a film for C4. It was the men who crewed them that fascinated him the most. Down in Brixham, Devon, they had four crew – skipper, mate, deckhand, and a cookie who was often only 12 or so. Theirs was an unremitting routine. Danger and death were never far away: it was the most dangerous job in the land. Yet they earned a reputation as supreme, quietly proud seamen, religious, brilliantly able to navigate without charts and survive just about anything. Except, maybe, falling in love with the town’s most complicated young woman.

INTERNATIONAL WOMAN’S DAY 8 MARCH 2024 - We explore the fascinating women and men who mobilised public opinion to get women the vote. And we peel away the Pankhurst monopoly to reveal something much uglier – a gender war, a class war and terrorism. And also an unexpected preoccupation with shopping. [Eight episodes]

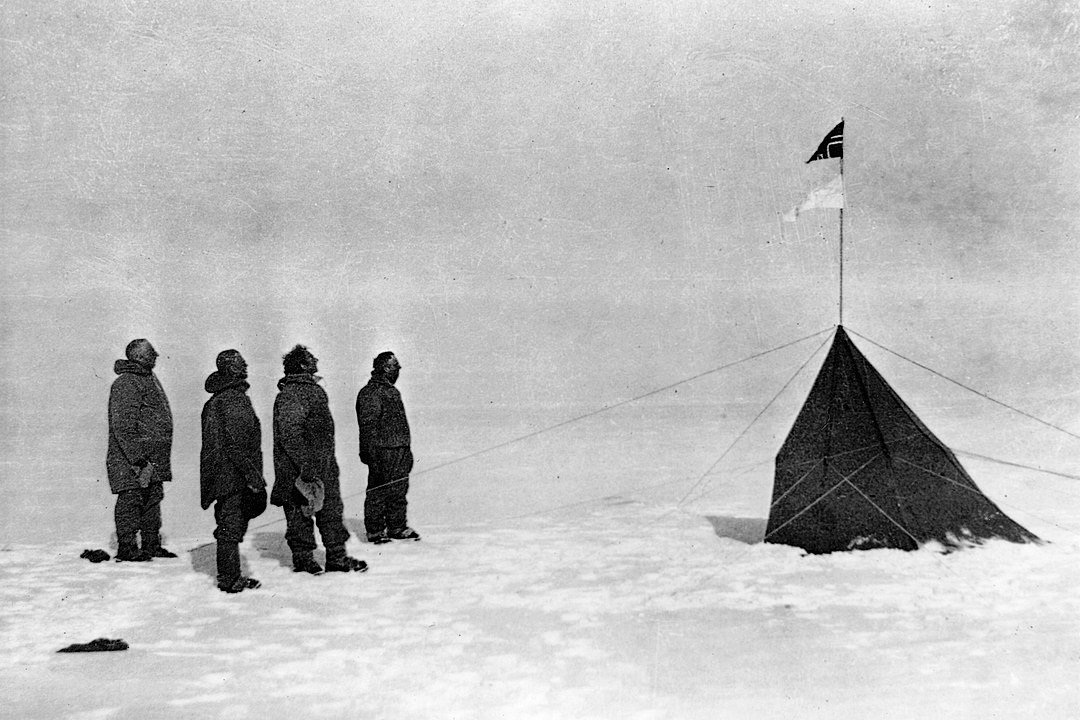

The race for the South Pole in 1911, between Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen and Royal Navy captain, Robert Scott, was mainly about personal pride. Scott’s failure arose not only from a litany of misjudgements, but also from a very toxic kind of Britishness: a haughty refusal to learn, a belief in spirit over common sense and the option for suffering over second place. This is what makes the story historically worth telling - because it would materially contribute to 880,000 service casualties on the battlefields of the Great War [4 episodes]

In 1908 and 1909 two white Americans, one black American Mat Henson, and six Inughuit: Ittukusuk and Aapilaq, Egingwah, Ootah, Ooqueah and Seegloo claimed to have reached the North Pole – a patch of constantly moving sea ice. US Navy Commander Robert Peary who led the later expedition spent the rest of his life trying to cover his own dubious tracks and to prove that the earlier claim on the Pole by his old companion Dr Frederick Cook had been a fake. Since the technology of the day made it impossible for anyone to prove they’d reached the Pole we ask what mystery drew them to risk madness and death nearly 500 miles out onto dangerously thin sea ice. It turns out to be a heady cocktail of American money, ambition and self-doubt. The Wild West on ice!

The coronation of King Charles III has prompted this humorous historical look at the British coronations. Since 1902, when Edward VII and his queen were crowned, the religious ceremony itself has drawn upon rites going back to the crowning of Anglo-Saxon kings. But reviving these old rites just belongs to an Edwardian fascination with a mythical Merrie England. And once you step outside all the solemnity of the Abbey, we are in a world that was entirely invented between the 1870s and the first world war. It was then that British royals turned into a strange mix of an oddly middle-class family that was given to stagey, mock-historical popular pageants, with an increasing display of military uniforms to boost Britain’s failing international image. Thespian imperialist Lord Esher, who headed the coronation planning committee in 1902, had very little time for the ordinary British people he called ‘millions of drudges’. He insisted that everyone in royal ceremonies – not just the military – had to wear a uniform. It was meant to distinguish them from the mere mortals who could watch from the sidelines. Ultimately these events were always about international politics. The coronation of Charles III occurs in the context of Brexit and deep economic crisis and carries as much international weight as anything that has gone before. [One episode]

If the wildness of the Wild West is a myth then it needs to be called out. Too many Americans (including a few presidents) have believed in an ‘atavistic relation’ between ‘a man and his gun’. We examine the history behind this justification of deadly violence. [Two episodes]

Exploration changed in the middle of the nineteenth century, when Henry Morton Stanley met Dr David Livingstone.

We discover that Livingstone isn’t remembered for anything he achieved. A missionary and medical doctor from a poor Scottish background – and an indestructible traveller - he learned to make accurate geographical calculations and used them to map a small part of Africa. Amazingly he did most of his successful exploration with an African team and backed by African funds. The Africans, it turns out, had their own good reasons to back him. Once the British government was involved, he got spectacularly next to nothing done at all. [Five episodes]

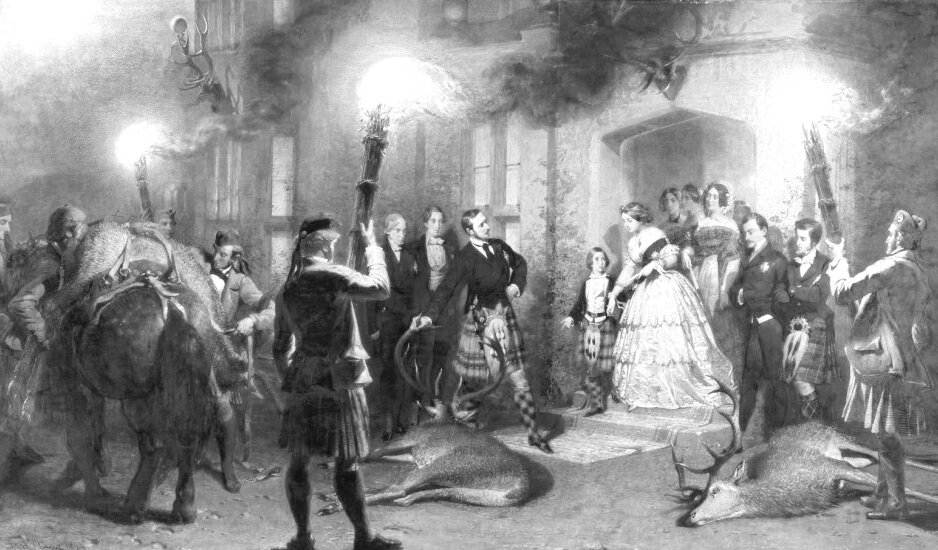

In 1983 Professor Hugh Trevor Roper claimed that Scottishness had been invented. We enjoyably demolish Trevor Roper’s theory and reveal that the commercialisation of romantic Scottishness in the nineteenth century had far deeper and darker roots than the manufacture of tartan and romantic fiction. [One episode]

Everyone knows that slavery was abolished in 1833 (in British colonies anyway) because of the moral campaign of William Wilberforce. But this is just the story told by his sons in a five-volume biography published after his death. In reality Wilberforce had been a saintly but often ineffective campaigner and the lead had really been taken by others. Much more important, in 1944 Eric Williams, Trinidadian historian (who’d got the top history first in his year at Oxford) demonstrated in Capitalism and Slavery that it was economic changes, and not moral campaigns that ended slavery: it ended because it simply no longer turned a profit. It’s a brilliant, persuasive book and sparked a debate that’s still not resolved. We consider both sides. [Five episodes]

An accessible podcast on Jon’s academic book Partisan Politics – looking for consensus in Eighteenth-Century Towns (Exeter University Press 2021). See on our Publications page for 45% discount. [One episode]

The economist John Maynard Keynes bought hundreds of Sir Isaac Newton’s manuscripts on spec at an auction and concluded that they were in fact detailed notes on the great 17th century mathematician and scientist’s reading and experiments in alchemy. He described Newton as ‘the last of the magicians.’ We look at the case for and against… [Two episodes]

On the evening of 4 November 1605 Guy Fawkes was found ready to blow Monarch and Parliament to Kingdom Come. But what reliable evidence is there, once we exclude the confessions extracted under torture? Was he a victim of the common practice of framing political enemies? [Seven episodes]

313 people were killed for their beliefs in England and Wales between 1555 and 1558, during the reign of the Roman Catholic Queen Mary Tudor. Most of them were burned at the stake.

But like almost all episodes in England’s Catholic history, modern scholarship shows that this one’s been badly misunderstood. We’ve been investigating it, not in any way in order to excuse what happened, but to try to understand it. We feel we owe it to the victims to get the story straight. [Five episodes]

A ménage a trois: was Henry more interested in the Pope and the Frenchman he called his ‘brother’, than either Anne Boleyn or Queen Katharine? We discover that Henry’s foreign policy has a lot more to answer for than we thought. [Eight episodes]

The Wars of the Roses never happened – or certainly not in the way Henry VII’s propaganda told it. Even the roses are an invention. Which is why we ask What wars? What roses? But the real question is, what on earth was going on in fifteenth century England? Or, more seriously, could this really have been the end of medieval England and the start of the modern? Well, the intriguing thing is, that when you peep over the edge of the fifteenth century, you discover that something very profound did in fact change. [Five episodes]

A whole lot of nonsense has been written about the invention of the modern Christmas. It was thought up by Washington Irving or Charles Dickens or Prince Albert. We just can’t resist attaching a famous name to things, especially if the name belongs to a writer or a royal. We deserve better than this. So here's our offering from the History Café Christmas Party! Have a good one. [One episode]