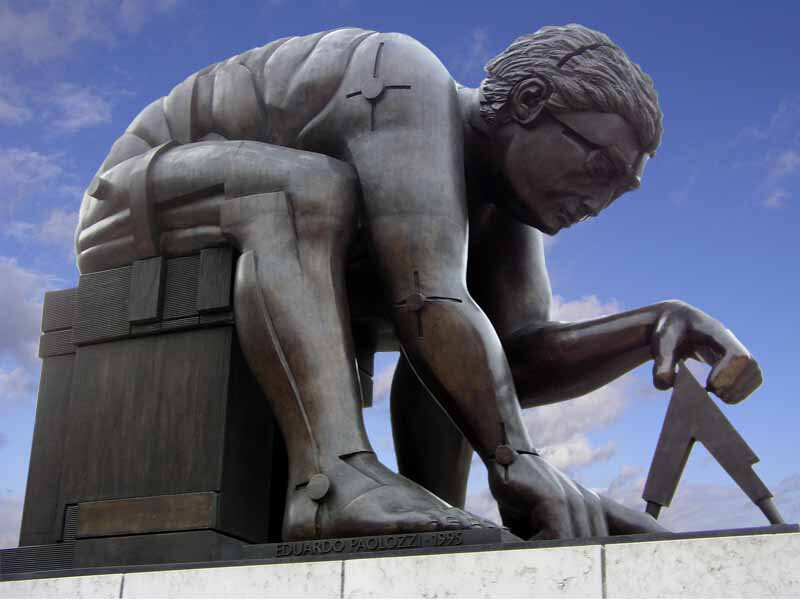

Isaac Newton: the last of the magicians?

The economist John Maynard Keynes bought hundreds of Sir Isaac Newton’s manuscripts on spec at an auction and concluded that they were in fact detailed notes on the great 17th century mathematician and scientist’s reading and experiments in alchemy. He described Newton as ‘the last of the magicians.’ We look at the case for and against…

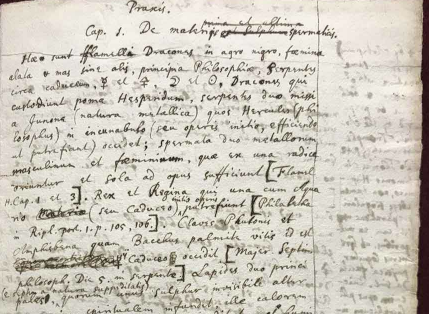

Newton the alchemist. Ep 1. The short answer to the question, ‘was Newton the last of the magicians?’ is, yes …. And also … no. Newton and alchemy turn out to be ‘a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.’ We toss a coin and take a heads-and-tails approach. In this podcast we argue that the alchemical experiments he undertook had nothing to do with magic. Newton’s alchemy now looks to historians like good science (although he would have called himself both a natural philosopher and a chymist). It was well conceived and measured and drew on the work of his contemporaries and of many men before him. And Newton was certainly not the last person in Europe to practise alchemy of this kind. Within fifty years of his death it would simply evolve into modern chemistry.

Having considered the arguments in favour of defining Sir Isaac Newton as an early 'scientist', we now consider the other side of the coin.

Newton’s best-known breakthrough – the identification of gravity – belonged not to the latest tradition of European Cartesian rationalism, but to a very English strand of occult philosophy. In fact it was only because Newton worked in this tradition that he was able to think of gravity as an unseen and mysterious force. Europeans like Leibnitz wrote the idea off as magic.

More striking, like other English philosophers, Newton believed that all this had been known to ancient thinkers going back to Noah, and spent much of his life trying to decode the myths and symbols they left behind. He was, he believed, the only man in his generation privileged to understand them. The last of magicians? Maybe.

The seminal read for modern Newton studies is JE McGuire and PM Rattansi’s ‘Newton and the Pipes of Pan.’ It appeared in Notes and Records of the Royal Society 21 in 1966 and moved things definitively on from the dry old debate, ‘was Newton a scientist or a magician?’ In the years that followed the colourful world of early modern alchemists was rediscovered, notably by Frances Yates in The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabeth Age (1979). It led to a gloriously romantic reinterpretation, most gorgeously in Morris Berman’s The Reenchantment of the World (1981). These are classics to read and enjoy, even if you should nowadays use with caution.

The notion that Newton saw the world primarily an alchemist grew at this time into an orthodoxy in the work of RS Westfall and BJ Teeter Dobbs. Alongside these we should put Michael White’s Isaac Newton. The Last Sorcerer (1998). The clue is in the title. Even so, it’s still the most accessible biography, something to enjoy on a train. Westfall is also still regarded as good to consult. But academically all the material from these years has been overtaken by heavyweight studies from scientist-historians who have argued very cogently that Newton was a methodical and hard-working chymist, just one of many in Britain, Europe and the American colonies.

William Newman has replicated some of Newton’s experiments and writes therefore with considerable authority, if not sadly with clarity. His important Newton the Alchemist (2019) has to rate as one of most awkward and unreadable history books you’ll meet. Shame. Laurence Principe’s The Transmutation of Chymistry – William Homberg (2020) is just as authoritative but is a great read. Newton hardly appears. But the book is the by far the best approach to ‘alchemy’ in this period, in this case seen from the perspective of the French. (Thanks to Professor John Henry, Edinburgh University - see below - for his encouraging response to the podcasts and for pointing out that we’ve mispronounced Principe’s name throughout. It should be more ‘Italian' sounding, and 3 syllables. We hope Professor Principe will accept our apology.)

To these Newton-was-not-a-starry-eyed-alchemist books add Paul Greenham’s unpublished Toronto PhD thesis, ‘A Concord of Alchemy. Isaac Newton’s Hermeneutics of the ‘Symbolic Texts of Chymistry and Biblical Prophecy’ (2015) online here. Greenham basically argues that Newton had a dryish academic interest in decoding ancient texts of various sorts, meshing his conclusions with his laboratory experiments.

But you have to fight the feeling that these historians of science sometimes mistake the bathwater for the baby. Concentrating on chymical beakers and burners sucks your attention away from Newton’s much more surprising approach to theology, history and what we now call physics. You could make a start on Newton’s other sides with Niccolo Guicciardini’s Isaac Newton and Natural Philosophy (2019), written by an historian originally interested in Newton’s maths. If you don’t try to understand the maths it’s a readable and balanced account. But it’s one of those books that’s much better read when you are familiar with most of the material already.

At some point you have to face Rob Iliffe and George E Smith’s Cambridge Companion to Newton (2nd ed 2016, chapters by Feingold, Iliffe, Gabbey and Stein.) And the much less readable Oxford rival, edited by Erich Schliesser and Chris Smeenk, The Oxford Handbook of Newton (published on-line chapter by chapter and growing since 2017, chapters so far by Biener, Brading, Schmaltz and, especially, Henry) This – especially from Oxford - is impressive, often oppressive stuff, which has little magic about it. For something a bit more fun look up Xiaona Wang’s unpublished Edinburgh PhD, ‘Though their Causes be not yet discover’d: Occult Principles in the Making of Newton’s Natural Philosophy’ (2019 – online here. It reopens the possibility that Newton’s mind was receptive to ideas we should nowadays not term scientific. You can read more from the Edinburgh faculty with John Henry and JE McGuire’s ‘Voluntarism and panentheism’ in Seventeenth Century 33 (2018). How fantastic that McGuire is still publishing on Newton more than fifty years after ‘the Pipes of Pan.’

So much for the main debate. If you’re still a fan of Keith Thomas’s Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971), then you should read Andrew Mandelsohn’s ‘Alchemy and Politics in England’ in Past and Present 1992 and put Thomas back on the shelf. Newton’s twenty-one years at the Royal Mint still seem to be waiting for their historian. Guiccciardini gives them just thirteen lines. There are a few microscopic studies of his attempts at manufacturing reform, such as Ari Belenkiy’s paper in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 2013. Thomas Levinson, Newton and the Counterfeiter (2009) concentrates on Newton’s pursuit of a well-known crook. Otherwise you might as well read White.

Finally Frederick Kyle Satterstrom’s Harvard undergraduate thesis, ‘Alchemy and Alchemical Knowledge in 17th century New England’ (2013) is here and gives a freshly sideways perspective. It’s worth a look because the American George Starkey was key to the work of Boyle and Newton.

For by far the best introduction to at least some of the science behind all of this, read Geoff Cottrell’s Matter. A Very Short Introduction (2019). Actually, Geoff also read our script for us and made some great suggestions. The mistakes, as they say, are however all our own.

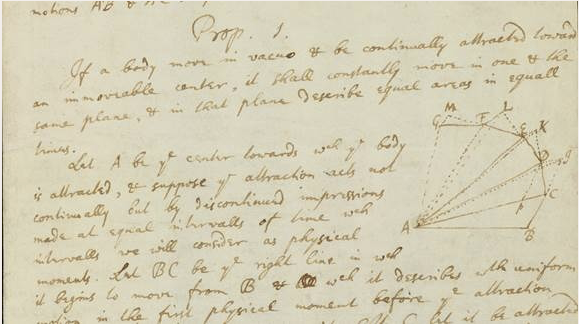

There are vast swathes of Newton’s documents online here. But unless you’re an experienced historian of science, you’re quickly going to vanish under waves of complexity. Dip your toe in but let the experts get on with their work.