Murder. Mystery at the North Pole

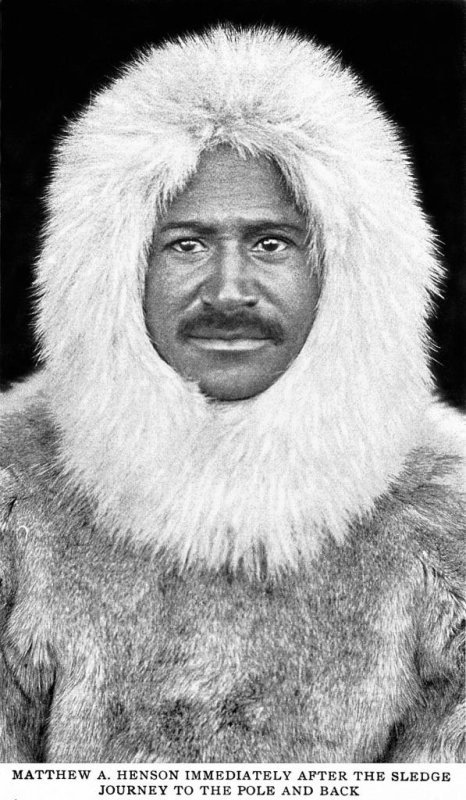

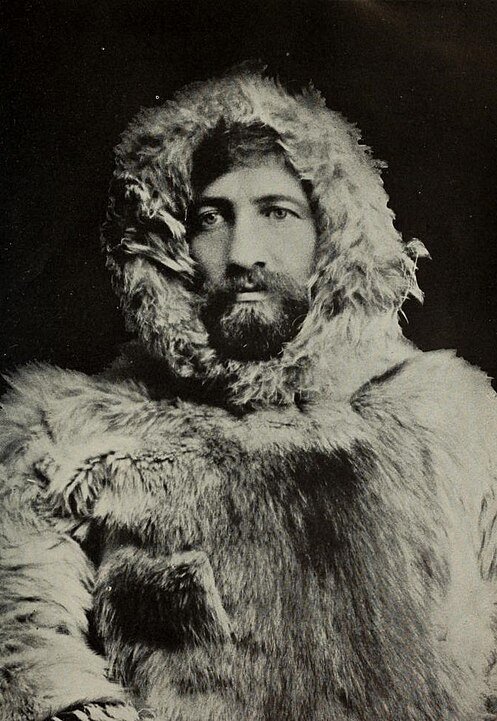

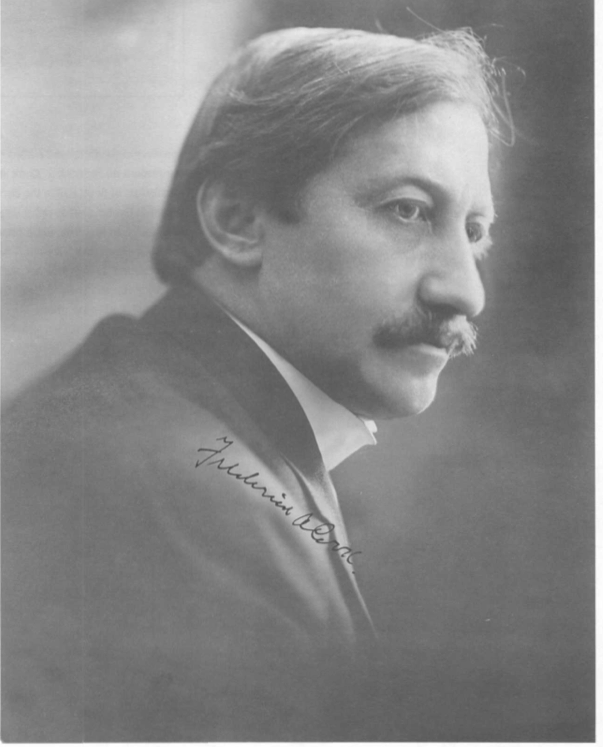

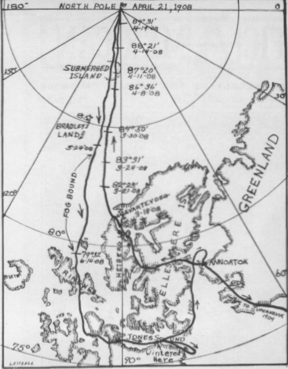

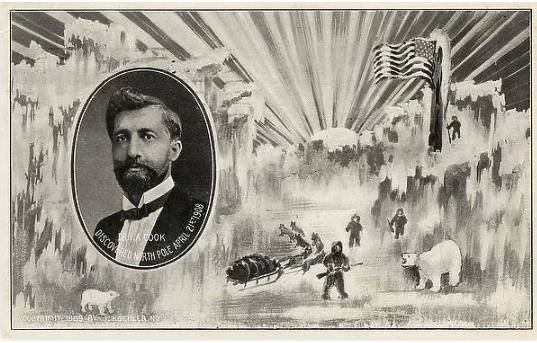

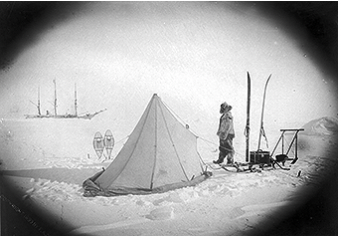

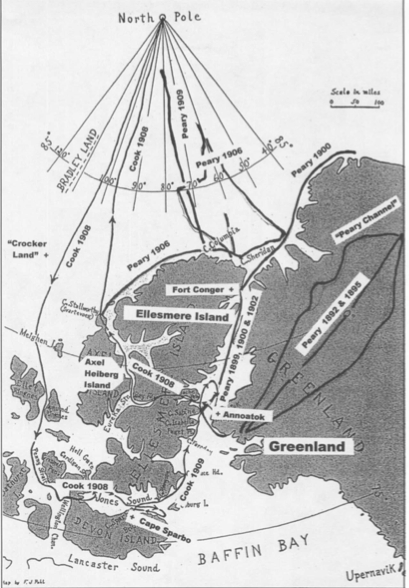

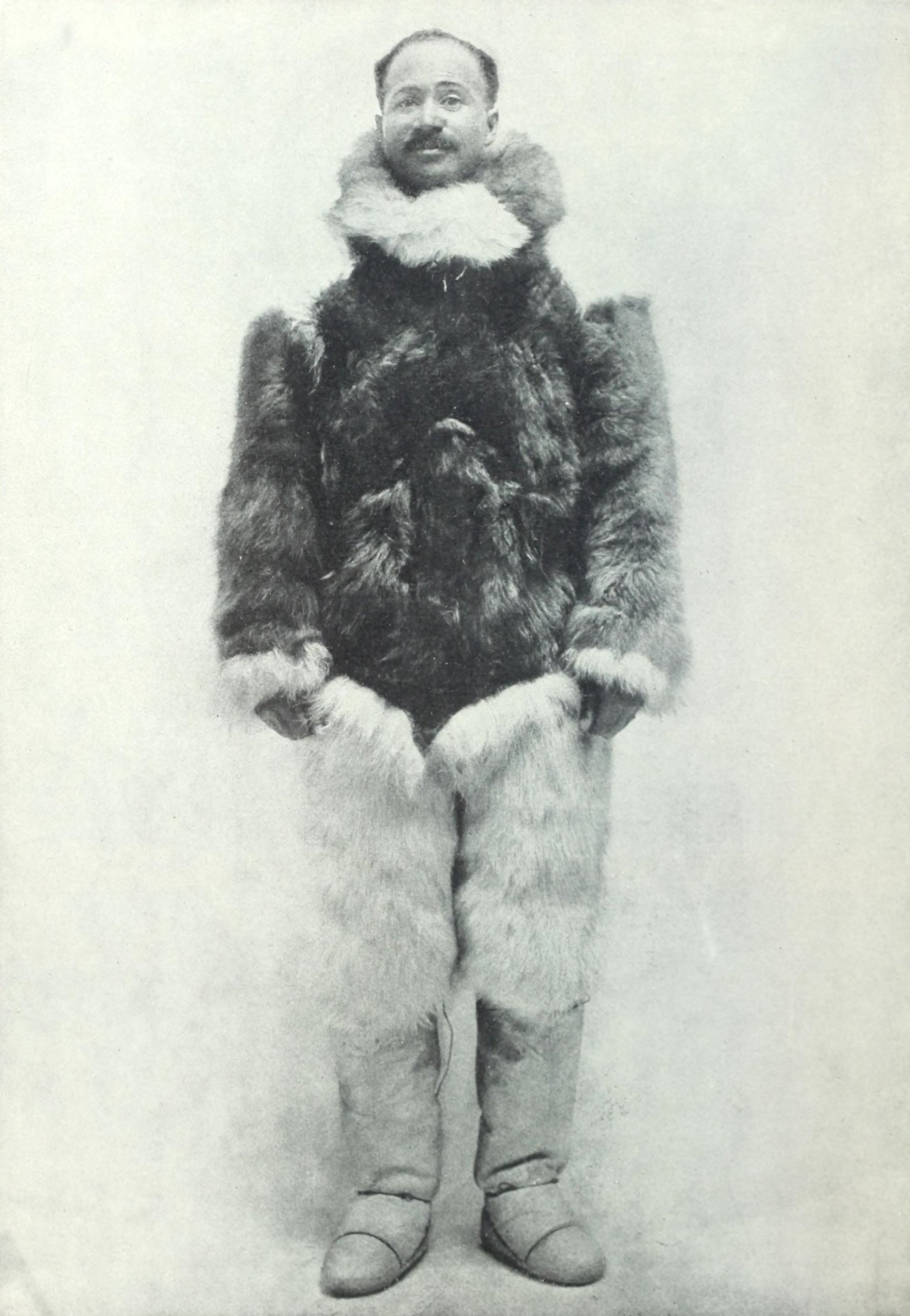

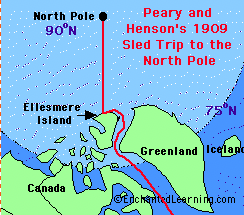

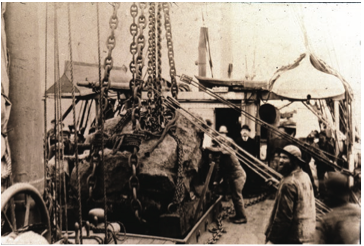

In 1908 and 1909 two white Americans, one black American Mat Henson, and six Inughuit: Ittukusuk and Aapilaq, Egingwah, Ootah, Ooqueah and Seegloo claimed to have reached the North Pole – a patch of constantly moving sea ice. US Navy Commander Robert Peary who led the later expedition spent the rest of his life trying to cover his own dubious tracks and to prove that the earlier claim on the Pole by his old companion Dr Frederick Cook had been a fake. Since the technology of the day made it impossible for anyone to prove they’d reached the Pole we ask what mystery drew them to risk madness and death nearly 500 miles out onto dangerously thin sea ice. It turns out to be a heady cocktail of American money, ambition and self-doubt. The Wild West on ice!

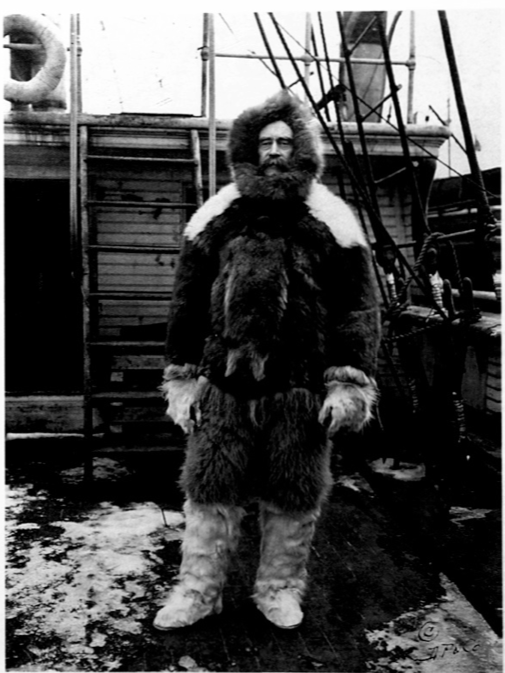

We may think the main controversy surrounding American, naval commander, Robert Peary’s claim to be the first to reach the North Pole on 6/7 May 1909 was whether he, and the other ‘invisible’ five men accompanying him, actually got anywhere near the Pole. However, it’s a much more complicated and sinister story than that….

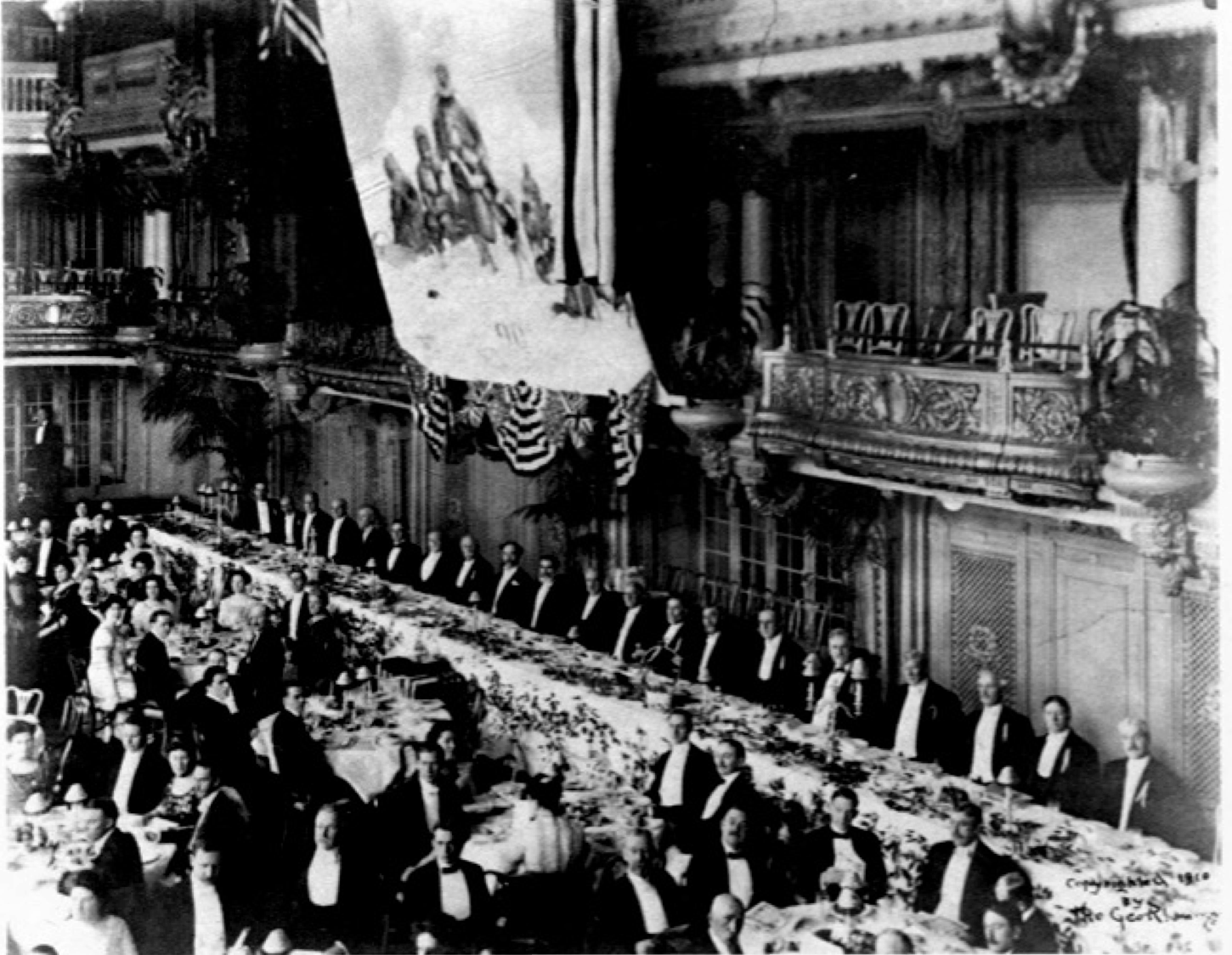

Robert Peary’s backers were the wealthy railway barons and bankers of New York. It didn’t matter to them whether Peary was the first to get to the North Pole or not. What mattered to them in 1909 was that he would say he’d reached the Pole, and then tell a strong, manly tale about it. In their eyes the future of Americans, as the tough frontier people, depended upon it. It may well have pushed Peary, a man who was known to be both ruthless and exploitative, towards murder…

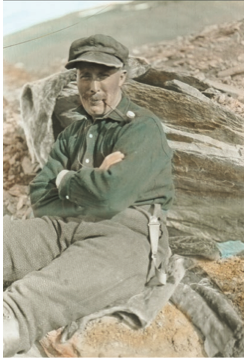

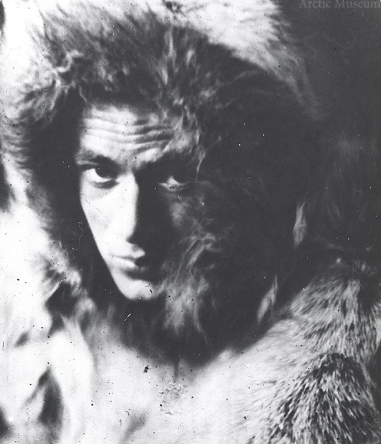

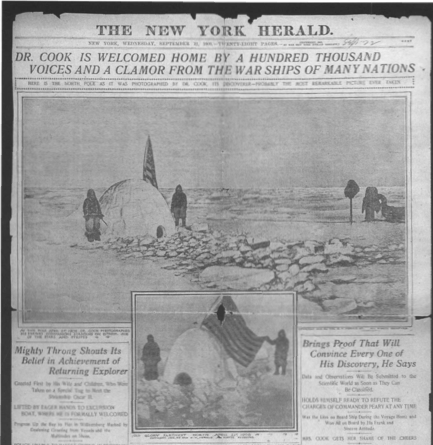

A full year before US commander Robert Peary claimed he had been the first man to reach the North Pole, a younger, medical doctor, also from America, had beaten him to it. Or so he told the press. His name was Frederick Cook and he had expedition history with both Peary in the Arctic and Amundsen in the Antarctic. He not only treated the Inughuit well but also returned with credible latitude readings and unique observations of the movements and character of the polar ice. None of which was unacceptable to Peary and his millionaire backers.

Did Robert Peary or Frederick Cook reach the North Pole first? In our 100th podcast, we weigh up what evidence remains after a ruthless campaign to destroy records and reputations. And we discover the new evidence that has begun to emerge from the most unexpected places.

Setting out to research the race to the North Pole is uncannily like stepping out onto the polar ice. The ground on which you are trying to make progress is being pushed this way and that by unseen currents and winds, and you very quickly find yourself falling through thin ice and drowning in untold fathoms of unaccountable detail.

Or, to change the metaphor, this subject resembles nothing so much as Jack the Ripper or the Gunpowder Plot. It has attracted a horde of outspoken – not to say angry - conspiracy theorists, whose enormous output very largely disregards the canons of historical method. Conspiracy theories make sweeping claims on the strength of small details from flawed documents, fundamentally misunderstood. At the History Café we strongly believe that the study of history is open to everyone. But there are times when you need a professional to keep your gaze on the bigger picture. And this is one of them.

You should start by reading anything by Lyle Dick, perhaps his ‘Robert Peary's North Polar Narratives and the Making of an American Icon’, American Studies, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Summer 2004), pp. 5-34. Lyle Dick, ‘The men of prominence are 'among those present' for him":

How and Why America's Elites Made Robert Peary a National Icon’, is one of a number of excellent essays in Susan A. Kaplan and Robert McCracken Peck eds., North by Degree: new perspectives of arctic exploration (American Philosophical Society, 2013). There are many other excellent examples of Dick’s work. He sets Peary in the key context of the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century crisis in American confidence. It’s also the background to Cook.

You could follow up with Michael F Robinson, The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture (University of Chicago, 2006). Robinson shows how the explorers’ narratives were always intended as romantic, armchair travel – one of the crucial insights that the conspiracy theorists miss. It’s still worth revisiting Beau Riffenburgh’s now venerable The Myth of the Explorer (Oxford 1974) which was the foundation text for this idea - establishing that the narrative was everything, while the facts came in a poor second place.

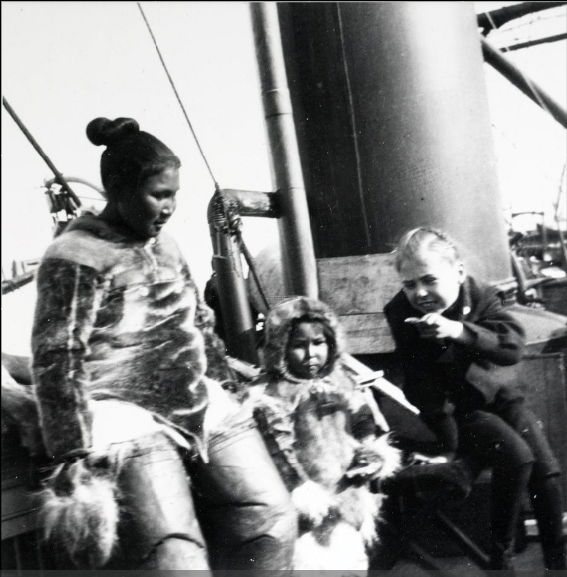

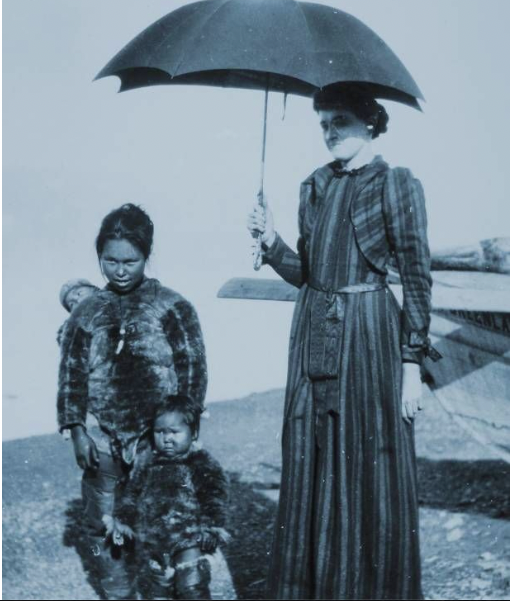

Shari Huhndorf, ‘Nanook and His Contemporaries: Imagining Eskimos in American Culture, 1897-1922’, Critical Inquiry, 27, 1 (Autumn, 2000), pp. 122-148 considers Peary’s disgraceful import of Inughuit as specimens for the American Museum of Natural History. You can pick up the rest of the story in Ken Harper, Give me my Father’s Body (NY 1986, 2000). Ken Harper has also contributed various stories – for example about Peary’s women (2009) and Ross Marvin (2023) to the Inuit newspaper Nunatsiaq News, which you can find online. Follow those with Renée Hulan’s shocking ‘Alnayah’s People: archival photographs from west Greenland 1908-1909’, Interventions 28.8 (2023) pp. 1088-1109 and the last shreds of respect for Peary and his men vanish.

The most telling collection of papers on Cook’s claim – and indeed on the broader geographical and ethnographical contexts of the whole story - are found in Frederick A. Cook Reconsidered: discovering the man and his explorations, Byrd Polar Research Centre Report 18 (1998 and here). It is the record of a symposium held at the centre in 1993, with contributions by specialists from all manner of backgrounds – including an oceanographer, a mountaineer, a specialist on the Inughuit and a Russian glaciologist. It includes not only a range of views but an impressive consideration of various kinds of evidence, moving the discussion from the shifting ice of Cook’s (and by implication Peary’s) own narrative to the more reliable ground of modern understanding of the arctic, its geography and people.

If you want a readable – and beautifully illustrated - account of Peary’s expeditions, coming from a frankly pro-Peary provenance, but without ducking all of the difficult questions - go to Susan Kaplan and Genevieve LeMoine, Peary’s Arctic Quest. Untold stories from Robert E Peary’s North Pole Expeditions (Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, 2019).

A fascinating, and much neglected contemporary commentary is Thomas Hall, Has the North Pole Been Discovered? (Boston and Toronto, 1917), which you can find on archive.org. It is far too detailed (and often speculative) to bear much reading. But dip in. Hall was an experienced navigator with (whatever some have tried to claim) no axe to grind. He indeed ran some personal risk in his public criticism of Peary. His analysis, significantly written from the navigational knowledge of the time, amounts to a damning demolition of Peary’s case. He is especially entertaining on the Congressional Committee’s investigation.

After all this you have to tangle with the accounts produced by the participants. Dierdre Stam, ‘Interpreting Captain Bob Bartlett’s AGS Notebook Chronicling Significant Parts of Peary’s 1908–09 North Pole Expedition’, Geographical Review 107 (2017), pp. 185-206 helpfully unpacks Bartlett’s journal. Donald MacMillan, How Peary Reached the Pole (Houghton Mifflin 1934, McGill-Queen’s 2008) is intriguing. It is a book written by a man who was, by then, an experienced and pro-Inughuit explorer. He ostensibly wrote it in defence of Peary, but it repeatedly throws doubt on what Peary claimed. It is illuminating to compare George Borup’s published A Tenderfoot with Peary (New York, 1911, 2020) with his hand-written journal (apparently written up soon after his return from the ice) which is at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee and here. Also important is Matt Henson’s account A Black [originally ‘Negro’] Explorer at the North Pole (New York, 1912, 1989). These latter accounts were written only with Peary’s permission; but even they raise significant questions.

And of course you should read the accounts published under Cook and Peary’s names. Peary’s is The North Pole: its Discovery in 1909 under the Auspices of the Peary Arctic Club (New York, 1910). Cook’s is My Attainment of the Pole (New York 1911). The 1913 edition of Cook carries an endorsement signed by a long list of contemporary polar explorers and luminaries and is online here.

Which brings us to Robert Bryce. You cannot study this subject without coming across his enormous output. Bryce is a librarian who has expended many years and an extraordinary ingenuity rooting out previously unknown documents, particularly relating to Cook. For this we are very much indebted. Sadly his commentaries then fall into the many traps of the conspiracy theorist. Bryce chews through the tiny details but ignores key issues of his documents’ purpose and provenance, and any of the broader context. The most striking example is a diary of Cook’s that Bryce discovered in Copenhagen, and which he then tries to use (largely on the basis of disputed dates and a cascading series of undeclared assumptions) to suggest that Cook was a fraud. Those who disagree – notably the contributors to the Byrd Polar Research Centre 1993 Conference - are brushed aside as part of a conspiracy. Best to steer well clear. But at the least, avoid getting caught in the trap of quibbling over details in documents that don’t bear the weight Bryce puts on them. That way Ripperology lies.

For contrast, dip into the (now sadly ageing) online resources of the Frederick Cook Society. Of course these usually back Cook’s claim. But they are often refreshingly candid. At least you can draw your own conclusions in a clear-headed way.