Nightmare in the Trenches (1914-16)

There are those who say that the Battle of the Somme (July-November 1916) was one of the British Army’s greatest achievements. They claim that - after the first day, with 57 000 casualties, more than any other day in the Army’s history – the British inflicted such damage on the German forces that they never truly recovered. But we show that this had not been the British Army’s intention. That first day, Commander-in-Chief Douglas Haig explicitly planned for a dramatic breakthrough. The slaughter that followed was a direct result of the British Army’s long history of failure to understand modern warfare or to learn from its errors since the war started in 1914. It did not possess the heavy artillery it needed. It was also a result of the blind snobbery of its officers. We throw their ghastly blunders into relief by comparing the brilliant – but little known - success of the French that day and of the few British divisions that copied what the French did.

1 July 1916. Had British Corps commanders understood machine gun warfare they would not have sent British infantrymen across No Man’s Land unprotected from the German machine gun crews. In fact we explain why the British army need never have been in the position it was in on the Somme, scrabbling about at the bottom of hills, peering up at German fortifications in all the strategic locations. We look at its refusal to take trench warfare seriously even though it had been around for 60 years.

Unlike the Royal Navy, the British Army proved itself over the course of decades incapable of taking new ideas on board: trench warfare, the machine gun and the tank to name a few. And at the heart of the problem was that too many men in the army refused to take orders. Not the rank and file, you understand, who were executed for any refusal to march into a hail of bullets. But the officers. The reason was that they regarded themselves as gentlemen – and gentlemen could not be bossed around.

The British Army wanted to throw men against machines. Its generals had not thought about how to cross 100-200 yards of open space with wire entanglements. They had been offered plenty of designs for armoured tractors with caterpillar tracks but had ignored them. It was Churchill, head of the Royal Navy, who eventually funded the development of the first ‘tank’. But they arrived late at the Somme and were so badly deployed they couldn’t save lives. And that wasn’t the worst of the problems the British army had created for itself.

On the eve of the Somme the British had far too few artillery guns, and most of the ones they had were the wrong sort. They needed five times as many heavy guns before they could launch an attack. The few big guns they did have were grossly inaccurate, sometimes missing a target by one mile. They were firing shells that were not fitted with delayed-action fuses which meant the German machine-gunners were safe in their deep underground bunkers. And yet British schoolchildren are still taught it was a surprise that the bombardment that preceded the infantry attack failed so catastrophically.

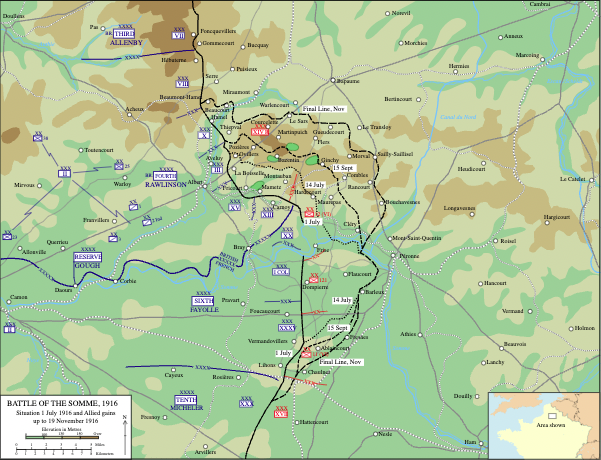

The French decided they only had enough artillery to attack on a 9-mile front if they were to neutralise the German guns so that their infantry were not needlessly slaughtered. Haig had fewer guns – enough for perhaps 4 miles of front – but he chose to attack across 16 miles. 57,000 British soldiers died on the very first day, 1 July 1916, and no ground was gained. The French achieved all their objectives and lost 1,500 men. This is not a story that’s usually told.

At the southern end of the line, next to the French, British units took all their objectives on the first day of the battle. They succeeded mainly because their maverick commanders had learnt from the French how to bombard the Germans accurately, putting them out of action long enough for the infantry to mop up. They’d also been assisted by the French big guns. By lunchtime some of these units were being served a hot meal in a newly occupied German trench. It’s a remarkable story the British Army has done its best to forget. Some military historians say, with all that French help, they cheated!

On 14 July 1916 senior officers finally decided to ignore Haig. At the Battle of Bazentin Ridge they put to use everything that was good practice and broke in to the German lines. But because junior officers at the front were not permitted to take a decision, and their commanders in their chateaux were hopelessly out of touch, it was never converted into a ‘break through.’ Another 9,000 lives lost for very little gain.

After the disaster of the Somme, whitewash was elevated to a new military art form. Haig and other senior officers lied in their accounts. Haig ultimately blamed the French. Haig was even promoted by his friend the King. But he got his comeuppance on 26 March 1918 when command of the British army was handed to the French. The defeat of the Germans would be masterminded not by Haig but by Ferdinand Foch.

Everything you thought you knew about the Somme changes when you read Peter Barton’s The Somme: a new panoramic perspective (2006). It’s full of never-before-seen reconnaissance photographs of the battlefield and diagrams of saps, dugouts and everything else. Barton shows beyond doubt how the commanders – except Maxse, Shea and Congreve - neglected new methods and weapons.

Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson’s The Somme (2005) disposes of many old myths. Get past the introduction - which tries to blame the politicians for what happened - and the rest of the book is as informative an account of the battle as you could want. After Barton, Prior and Wilson you won’t need any other general accounts. For the 14 July attack, see TR Moreman, ‘The Dawn Assault – Friday 14 July 1916’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 71 (1993), pp. 180-204.

The battle looks completely different when you see it through the eyes of the other armies. Ian Sumner’s The French Army (1995) is a simple introduction. William Philpott’s Three Armies on the Somme (2009) introduces you to both the French and Germans (and tries doggedly to take a balanced view of Haig). If you want to go further, find Jack Sheldon’s readable The German Army on the Somme (2005) and Elizabeth Greenhalgh’s not too difficult The French Army and the First World War (2014). If you still want more detail, then look up Robert Doughty, Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War (2005).

On the profound failure of the British to grasp the importance of artillery, go to Jackson Hughes’s unpublished University of Adelaide thesis, available on-line, ‘The Monstrous Anger of the Guns. The Development of British Artillery Tactics 1914-1918’ (1992). See also as a contrast Jonathan Krause, ‘From Balletics to Ballistics: French artillery 1897-1916’, British Journal for Military History 5 (2019),

There are several texts about British Army officers and their reluctance to understand anything new. Try Robert Foley, ‘Dumb Donkeys or cunning foxes? Learning in the British and German armies during the Great War’, International Affairs 90 (2014), pp 279-98. Equally critical is Tim Travers, ‘The Hidden Army: Structural Problems in the British Officer Corps, 1900-1918’, Journal of Contemporary History 17 (1982), pp. 523-44. See also John Ferris’s chapter on British observers at the Russo-Japanese war, in John WM Chapman and Chiharu Inaba, Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War, vol 2 (2007). For Jean de Bloch’s analysis of modern mechanised warfare – which British officers haughtily ignored - see Grant Dawson, ‘Preventing “a great moral evil”: Jean de Bloch’s The Future of War as Anti-Revolution Pacifism’, Journal of Contemporary History, 37 (2002), pp. 5-19.

For a more sympathetic (if, in our view, less convincing) account, try Aimée Fox, Learning to Fight. Military Innovation and Change in the British Army 1914-18 (2018), though her 2015 University of Birmingham thesis, ‘Putting Knowledge in Power’, available on-line, is more informative. A similarly sympathetic account of the 1912 British army exercises is Simon Batten, ‘“A school for the leaders”; what did the British army learn from the 1912 army manoeuvres?’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 93 (2015), pp. 25-47.

Jim Beach’s Haig’s Intelligence: GHQ and the German Army 191601918 (2013) has a very revealing chapter on the Somme. You can follow the story of the first tanks in John Glanfield’s The Devil’s Chariots (2001). Christopher Baker-Carr’s story, From Chauffeur to Brigadier published in 1930, was republished in 2015.

Peter Simkins, Kitchener’s Army (1988) is all you need on the volunteers who fought at the Somme. The easiest place for British eye-witness accounts is Lyn Macdonald’s now rather old Somme (1983). Sheldon has many from the German side.

There are several biographies of Haig, often setting out to give him the benefit of the doubt but ending up agreeing that his leadership was a disaster. Try JP Harris, Douglas Haig and the First World War (2008) or Gary Mead’s The Good Soldier (2007). Haig’s war diaries – with good notes on how he later changed them – have been edited by Gary Sheffield and John Bourne (2005). Look up the attempt to get rid of Haig in AJA Morris’s Reporting the First World War (2015). There has also been a debate about exactly what Haig thought he was doing on the Somme. See a summary from one point of view in William Philpott, ‘Why the British were Really on the Somme’, War in History 9 (2002), pp. 446-71.

For a contrast, read John Baynes, Far from a Donkey (1995) which is a conventional biography of Ivor Maxse. Also revealing is Elaine McFarland’s ‘A Slashing Man of Action’ (2014), a biography of Aylmer Hunter Weston, which is available online.

Online try here but make sure to double check any details. This website has maps and a detailed account, though it lacks the French and German perspectives. This is a fun account of the making of the first tanks in Lincoln.

Above all, go to the Somme. Use a tour company, though be aware that many use ex-soldiers as guides. Their insight can be fantastic. But they are inclined to defend the Army, without knowing recent scholarship on the battle or the other armies.